Woman In Grass

This interview was conducted between Brackett Creek Exhibitions (Tessa Granowski) and Ellen Khansefid on May 1, 2022 over the phone.BCE: I'm with Ellen Khansefid, it's May 1. Wake up, wake up, first of the month, pay your bills. So, we'll just talk a little bit about your studio practice and the show coming up in New York and Montana, maybe you can even relive a horse ride.

EK: Wow. Yeah.

Ellen riding a horse in Montana

Ellen riding a horse in MontanaBCE: What does a day in the studio look like for you?

EK: Usually when I first get in, I try and clean up. I usually don't clean at the end of the day, so I like to tidy up and start with something easy that I see results from quickly. And yeah, I usually put on the old Crocs. I charge the Juul. I make some tea. Then I just kind of look around the studio and see what I should work on that day.

BCE: Because you have kind of multiple paintings going at one time, right?

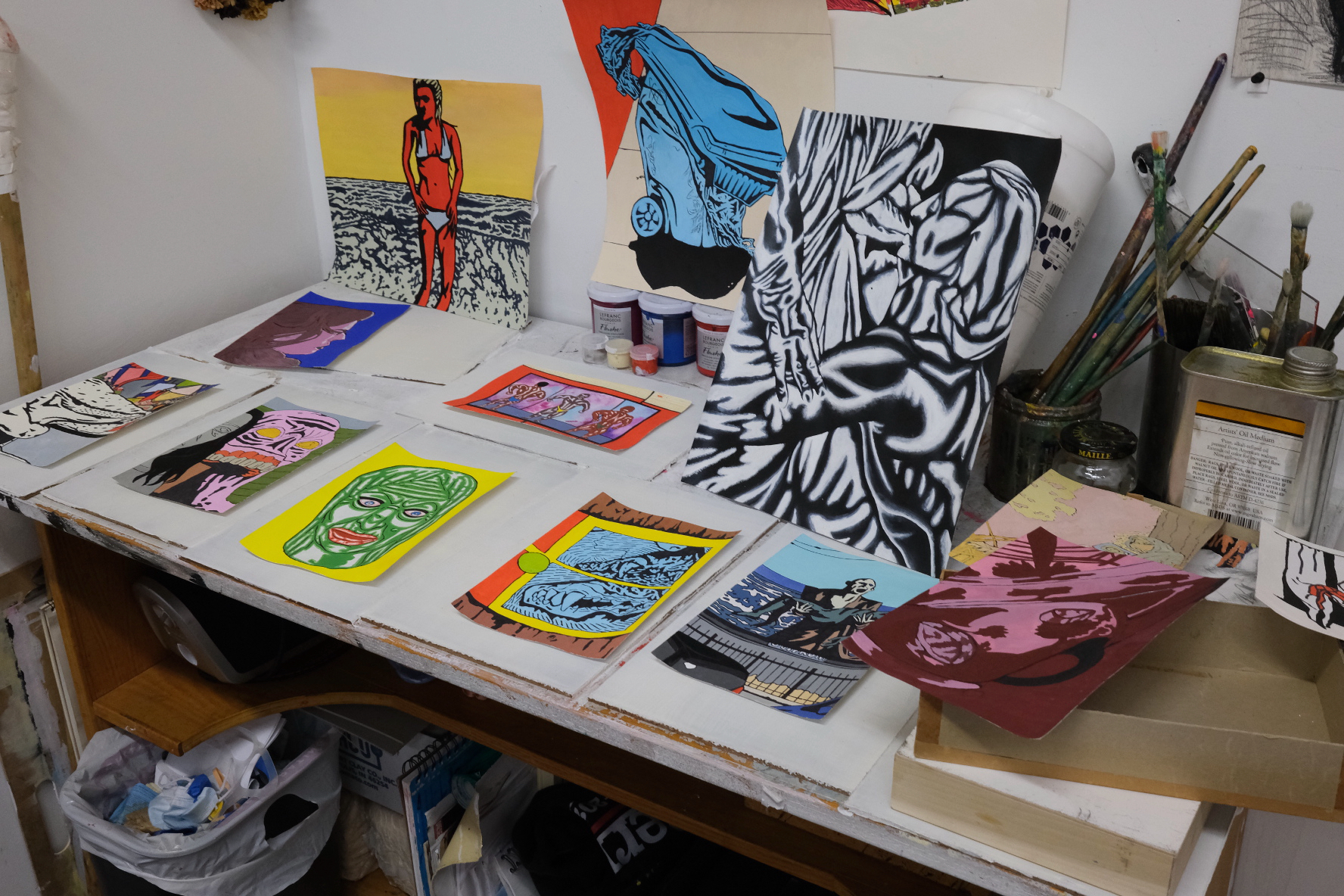

Ellen Khansefid studio

Ellen Khansefid studioEK: Yeah. I usually have a series of drawings going and then a couple of paintings going at the same time. I usually try and work out on one thing a day, so I don't really switch between them throughout the day. But yeah, I usually work maybe afternoon, the evening and usually listening to something like an audio book or the worst music you've ever heard.

BCE: Like Justin Bieber? Or I don't know. What's the worst music in the world?

EK: Well, I don't actually think anything's bad if I like it.

BCE: No such thing as a guilty pleasure in your book.

EK: Yeah. No guilty pleasure. I don't know, like old pop music or N*SYNC. I've been listening to N*SYNC like crazy.

BCE: Does that kind of just get you pumped up for yourself in the studio?

EK: I think of music kind of as a meditative sort of thing when I put a song on repeat. So, I almost put myself in a trance. And that's if I'm in a good mood… If I am having trouble, I'll put on an audiobook to kind of leave me more in the lizard brain.

BCE: Yeah. So sometimes when you wrap up from the studio, you walk over sometimes to Forest Lawn Cemetary,?

EK: Yeah. If I ever feel stuck or really tired, I'll walk down San Fernando Road to the Cemetery. It's so beautiful. And I usually take a lot of photos when I'm walking there and in the Cemetery.

BCE: Is it kind of more an interest in people mourning or is it like the wild variety of sculptures and headstones and landmarks there?

EK: It’s more about the place itself. The creator of Forest Lawn, Hubert Eaton, wanted to make that place was like the Disneyland of Cemeteries. Like it's this sacred place but then there's a statue of David and really wild mosaics and a labyrinth. It's this place where you're not supposed to have a good time, but you're having a great time. I think I want my work to be kind of like Forest Lawn.

BCE: Like a dark optimism, or a bright pessimism.

EK: Yeah, the Yin and Yang.

BCE: I was amazed when you took me there and we got to see one of the world's largest paintings, like 200 feet long...

The Crucifixion painting by Polish artist Jan Styka, 195 foot long/45 foot high on view at The Forest Lawn Cemetery in Glendale, California

The Crucifixion painting by Polish artist Jan Styka, 195 foot long/45 foot high on view at The Forest Lawn Cemetery in Glendale, CaliforniaEK: Yeah, one of the world's largest paintings is down the street from my studio in Glendale!

I think Forest Lawn to me is a place like The Museum of Jurassic Technology or the Velaslavasay Panorama. They all kind of exist in the same world to me where it's kind of the best art in its own world and it will exist whether or not anyone sees it.

BCE: What's the Velaslavasay Panorama? I never encountered that in Los Angeles.

EK: Well, the big painting that we saw at Forest Lawn of the Crucifixion was made originally as a panorama, which functioned sort like an early movie. As you walk around and look at the painting, it becomes illuminated in different places and reads chronologically as a story. It was like a big form of entertainment before movies. But the Velaslavasay Panorama is still on the top floor of this old movie theater in Pico Union and it’s in a dark room, with a 360 degree view of a painting. And they change it every year or so.

BCE: Wow.

EK: Yeah. I think the last one I saw depicted a village in China. They apparently had Chinese artists come and paint this village and the lighting would change from night to day. There's also a replica of an Arctic scene, like some sort of Hunter's cabin on the first floor. It's in a little wooden room and you go in and they have the wind sounds playing and you can look out the window and see the tundra. It's really wild.

BCE: Wow. That’s such a Hollywood idea.

EK: It's so Hollywood. That's what I love about being in Los Angeles. It has these totally benign looking places in strip malls that have the wildest shit you can think of on the inside.

BCE: Totally. So, you grew up in Los Angeles. Did you grow up going or discovering some of these places on your own, or did somebody take you to them?

EK: I think when I was about 13, I started kind of exploring on my own more growing up here. I went to the Hammer Museum with my parents sometimes, but they weren't really into art. I mean, not having a car in Los Angeles and trying to find things to do as a teen with no phone... you end up in some weird situations. But it was fun. Like, exploring and trying to find different forms of art. I never went to galleries growing up, but The Museum of Jurassic Technology was down the street from my high school, so I ended up going there a lot.

BCE: That's awesome. My idea of growing up in Los Angeles came purely from reading Eve Babitz’s Eve's Hollywood or Robert Irwin's childhood in seeing is forgetting the name of the thing one sees, where there are they have these totally sun-bleached teenage wasteland experiences… you may end up on the beach with a bunch of strangers or in a sunny, but rough, gang scenario out there.

EK: Yeah totally. And also there’s Francesca Lia Block who wrote Weetzie Bat. I don't know if you ever read that book.

BCE: No, I haven't.

EK: But it's all this candy-colored, high-saturation world of Los Angeles, which really influenced me growing up. You can just grab a coke, go in your friend's cool car to the beach, watch the surfers and eat weird food.

BCE: You can get kind of blissed out easily.

EK: Yeah. And it’s easier to ignore everything that isn't in that world.

BCE: You can always just look up at the palm trees, even if there's, like, a thick layer of smog.

EK: Yeah. Smog is the supporting character.

BCE: The antagonist, which we can ignore. Going back to these weird Hollywood-like spaces... that made me think of the Marciano Art Foundation, which is not open to the public anymore. It was so short-lived. But did you see that first show with Jim Shaw where he repurposed the Masonic Temple backdrops?

EK: Yeah. That show was amazing.

BCE: There’s like this whole underground of painted scenery. I feel like that's Los Angeles. You step inside a normal, boring-looking building and you're transported to a new artificial space.

EK: Yeah, totally. And it does feel like growing up here, you could step into any building and there's like a backdrop.

BCE: I noticed a lot of the taquerias had sceneries painted on the walls too--whether it was the ocean, the mountains, or some mythic ancient hero.

EK: Yeah. You can really travel the world here by going to different burrito spots. I think Los Angeles actually has the most murals in the world here or something, or at least in America.

BCE: Makes sense. So, I noticed from the Via Sanborn & Sunset show at BOBBY LA last summer, that part of the inspiration for the show came from Agnes Varda's Mur Murs movie about LA murals. Do you want to talk about that show and the collaborative sculpture you made with Marisa Marofske?

Ellen Khansefid & Marisa Marofske, 1*800 Bliss-Place, 2021, Concrete, Wood, Acrylic, 35” x 11” x 22”

Ellen Khansefid & Marisa Marofske, 1*800 Bliss-Place, 2021, Concrete, Wood, Acrylic, 35” x 11” x 22” Image courtesy of BOBBY LA and Michael Lombardo

EK: Yeah. That Varda movie was so beautiful, and it was about how much of the character of Los Angeles gets shown through these murals, especially just neighborhood murals. And I worked on that show, Via Sanborn & Sunset with Marisa Marofkse, Michael Lombardo and Erika Alfonso, and we all live in Los Angeles. We all have a similar appreciation for that type of wall art, like the painted blinds...

BCE: Right. The murals and the backdrops of Los Angeles.

EK: Yeah. And I worked with Marisa on a couple of concrete sculptures in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and we went through an ice storm and some other rough times on that trip, so when we came back to LA, we were really thankful to see the sun again.

BCE: And even the strip malls.

EK: Oh, yeah. Strip malls are the heart of the city. Those signs, I feel like every artist in Los Angeles has been influenced by those signs. They're the craziest, most beautiful thing in Los Angeles.

BCE: And I noticed this in moving from Los Angeles to New York… in New York my observations or photographs come from a sidewalk or the subway. And in LA, everything was from window of my car. The strip mall signs are the ones that you can lean out your window and stare at while you're stuck in traffic, right?

EK: Totally. I take so many photos from my car window. It’s the perfect way to get a snapshot of some bizarre, insane interaction.

Ellen’s car photography

Ellen’s car photographyBCE: Yeah, I definitely saw a lot of those when I worked in Inglewood and Gardena. Also, some incredible murals are down there. Instead of printing a sign for the store, some businesses would hire a sign painter to paint all the appliances that they sold on the side of the store.

EK: It's amazing. I mean what else do you actually need?

BCE: Why even have photography, actually, if you can just paint a vacuum cleaner?

EK: I mean, how do you think the vacuum cleaner should look?

BCE: I want to see both what we're selling, but also your idea of what we're selling. [both laugh] People also frequently told me to be careful and keep my eyes on the road because I had so many photos out the car window. I don't know if you get the same reactions.

EK: Everyone who takes photos while they are driving is like, listen, it's a horrible thing to do. I'm like, you know what? I’m really good at it. I do take photos when I'm driving, but no problems yet.

BCE: Yeah. You're like, I have two eyeballs for one reason.

EK: God gave me two hands for a reason. And you are never going that fast in your car anyway.

BCE: Not at all. Even on the highway, it's just inching along.

So, back to Via Sanborne & Sunset, the concrete sculpture that you and Marisa made was one of those strip mall signs, right? Was it a specific strip mall sign near you?

EK: Yeah. I was on a walk from my studio, and I walked up to Glendale and there's, like, these two twin signs on Chevy Chase and Brand. But those were taken from a strip mall in Glendale that was particularly beautiful.

BCE: I love it. So do a lot of the kind of drawings or paintings that you're making come from photos of some type of observation?

EK: Yes. Most of the work I do starts in drawings, and most of the drawings start from photographs I take. And I take so many, all the time. I have, like, 82,000 photos on my phone. It's ridiculous.

BCE: Wait. I kind of want to look how many I have. I feel like it's disgusting… Okay, I only have 31,000.

EK: I mean, that's still a lot. 31,000 images is crazy. That's crazy. Like, if you told any of our grandparents that one day, we would have 30,000 pictures on hand at all times, I think they’d find it hard to believe. There was a Norm MacDonald joke where he says, there’s like one photo of my great-grandfather. And in the future, people will be able to say, hey, do you want to see 100,000 photos of my great-grandparents?

BCE: [laughs] Where else do you go on walks for inspiration?

EK: Wherever my body is, is where the photos start to happen. The doctor's office a big source of inspiration. I mean, I feel like doctors always want people to feel at ease, so they put up art or signs, and it always ends up looking deranged.

BCE: It's never truly comforting because at the end of the day, they're a doctor, so they're already deranged. They've centered their life around being okay with seeing blood and guts and death and sickness.

EK: Yeah. Maybe doctors should curate a show or something. It would be pretty cool.

BCE: I would see that for sure.

EK: But, yeah, wherever I'm at, I'll take a photo. I love to go and walk. I live sort of near Silver Lake, and there's these great hills… and a lot of coyotes.

BCE: Oh, yeah.

EK: They're kind of freaky when they're in packs. I always see them in packs of five. They'll usually leave me alone but can be kind of intimidating.

BCE: Yeah. I feel like the perspective on coyotes can shift quickly, like, oh, do you have a small dog? Probably don't like coyotes.

EK: Yeah, it's wild. That's the Mayor of Silver Lake. Coyotes, for sure.

BCE: I like this play that we're putting together. The Los Angeles play with the full cast of characters.

EK: Yeah. We have the smog and the coyotes.

BCE: The palm trees, the murals. What about R. Crumb? He’s been a big source of inspiration for you, a California character, maybe not Los Angeles… Where did you first encounter his work?

EK: I don't know where I first saw his work, actually. I feel like if you're into sub-cultures, as soon as you turn, like, 14, you find out about R. Crumb.

But, yeah, I got really into indie comics and punk indie film as an angsty teen. I really identified with him being so disgusted with the world and so perverted and alienated. And also with Daniel Clowes, the writer of Ghostworld.

BCE: Oh, I love that movie.

EK: Yeah. I mean, those were huge influences. It was influential because that was my life, and I just saw it identified so clearly, even by a man from Chicago. It was crazy, but it was like exactly what growing up felt like. And they really romanticized the outsider and the weirdo in a way that I identified with and glorified. But I think it ended up holding me back as an early adult because I didn't take anything seriously. And I thought that being a perverted piece of shit was cool.

BCE: Yeah. I think R. Crumb would maybe even say that it held himself back. I think I read something where he was like, I finally have let go of being so utterly obsessed with sex.

EK: I think he's probably lying to himself. [both laugh] Yeah. But he was just such a hater. Like, I thought that notion of being an outsider was so right and so true. And I was like, yeah, the world does suck. But it really doesn't. It's not a true way of viewing the world. I think it's just like a defense mechanism, obviously. But it doesn't mean it's right. There are no outsiders, really. You're not special for thinking these things. Everyone feels alienated sometimes.

BCE: Yeah, and would it actually be more subversive to make something mainstream that everyone is wants to look at?

EK: I mean, his influence has been so big that he has entered the mainstream in a way that John Waters has. Over time, the influence is so big that it can't help but be absorbed into the mainstream. I think sometimes the more specific, niche the things are in art, the more relatable. I do like the idea of sort of like populist mentality. It doesn't have to be so pretentious. I would want people to appreciate work that is not just meant for people with MFAs. I mean who cares? I should be able to appreciate it.

BCE: Yeah, totally. So, I've been reading Robert Storr’s Interviews on Art recently, and I saw that he curated a show at David Zwirner in 2019 with R. Crumb that included William Hogarth. And that reminded me of studying Hogarth's print series, “A Harlot’s Progress”. Do you know that one?

EK: I don't think I do. I know him. Let me see…

William Hogarth, “A Harlot’s Progress” Plate 3 of 6, courtesy of Wikipedia

BCE: It's such a wild series. Hogarth made these in London around the mid-1700s. But it was a similar early example of something like we are talking about. So, this woman arrives in London seeking respectable employment and and then is quickly taken in as a prostitute and ends up getting syphilis and dying. And it's like six different etchings of the whole progression. And apparently that print was extremely popular, which is funny to think about that lots of families in London wanted to buy prints about a prostitute with syphilis who dies.

EK: These are totally wild. Yeah. I think people are always curious about fringe culture. It's so dramatic.

BCE: Exactly. And Max Beckman is another artist we have talked about that you admire. He’s someone else who painted really violent or sexual scenes, but at the same time, they are really beautiful images.

EK: Yeah. I mean, those are all such beautiful paintings and they're so graphic, both formally and in their content. That’s what I strive to make… something that can exist on both planes. It's like kind of a dark or funny or violent sort of thing that's also just like a beautiful painting.

BCE: Yeah, totally. So, one of the paintings you were working on last time I was in your studio is based on an Arnold Schwarzenegger woman's workout book, yes?

EK: Yeah. “Arnold's Bodyshaping for Women“.

BCE: In case you wanted to be a female Arnold. Were you inspired by that book because of all the different postures or positions and just kind of the weirdness of women who have their hair done and down and are trying to get buff?

Page from Arnold’s Bodyshaping for Women

Page from Arnold’s Bodyshaping for Women R. Crumb, Untitled, 2002

R. Crumb, Untitled, 2002Ink and correction fluid on paper, 14 x 11”

Image courtesy of David Zwirner

EK: Yeah, there's definitely an appreciation for the Camp of it, like getting dressed up and contort your body for some sort of self-improvement, which I think is always funny and weird. But I don't even lift weights anymore because I got obsessive about it.

BCE: Really?

EK: Yeah, I have a pretty obsessive personality and I got a little too into the fitness thing. It's sort of like an OCD thing. Like, I need this number of reps in these body parts every alternating day, and if I don't do them, then something bad is going to happen.

BCE: Yeah. I remember you had some kind of workout routine in Montana and you always got it done, even if you were like, smoking a cigarette while doing a squat.

EK: The compulsion! I will stop for no man, no situation! I will get my crunches in! Yeah. I switched to yoga to try and chill out a little bit. It's funny to watch, but you can always tell some of these yoga instructors are, like, really battling with their own OCD. They're really relaxed and say things like “It's okay if you don't do it perfectly. I promise if you don't do it perfectly, you're going to be okay. Don't worry about it. It's okay. Breathe.”

BCE: [both laugh] Okay. So, do you want to talk a little bit about the print that you made in Montana, Woman in Grass, that will be in the upcoming show? When did you make it? Where did that come from? Were you in the grass?

Ellen Khansefid, Woman In Grass, Edition of 10, 44 x 30.5”, acrylic, 6-color silkscreen

Ellen Khansefid, Woman In Grass, Edition of 10, 44 x 30.5”, acrylic, 6-color silkscreenEK: Yeah. So, I started that print the first time I visited Matt in 2019. And I had been working on a series of paintings in LA that were sort of based around this cartoon figure of this blonde, pink woman. And the first time I visited Matt in Montana, I was, like, blown away. I couldn't even process how beautiful Montana was.

BCE: What time of year was it?

EK: It was in September. So, it was a little bit cooler, but it wasn't winter yet. But anyways, I feel like whenever I go there and I've tried drawing from life but I can't process it. When I made that first screen print, Woman in Grass, it was sort of like trying to process the nature that I was seeing in the way that my brain works in this flat, graphic way. Yeah. We were talking about sort of dark humor earlier. I think that's something that I work with a lot. And in that screen print, I did think about the nude in nature. It's supposed to be confrontational.

BCE: Yeah. It's a powerful lady. That’s always scary.

EK: Yeah. I kind of was thinking about blowjobs a little bit when I was making it, like, she's kind of on her knees with a demented smile.

BCE: Yeah. A wild woman that you would encounter while hiking in the mountains.

EK: Like in a hypersexual, hyperreal sort of cartoon way. But it was so fun working on that print. I mean, I had a lot of help from Matt on that.

BCE: Had you done screen printing before?

EK: I did a little bit of screen printing at RISD when I was there. I actually made some Cheetos bootleg activewear.

BCE: Oh, my God, amazing.

EK: So yeah, I've done a little bit of screen printing, but Matt has his sort of own wild cowboy style out there, which is fun.

Woman In Grass next to drawing study in the studio at Brackett Creek, Montana

Woman In Grass next to drawing study in the studio at Brackett Creek, MontanaBCE: Really fast and loose. Do you think you've been able to process the beauty of Montana now that you've been back a couple more times?

EK: No. I flip out every time. The last time I was there, last summer, when I stayed for like a month, I made that series of gouache paintings that will be in the New York show based on photos that I had taken around Montana. And I remember going on walks by myself and sitting in that field down the way. And I think there was a fire from Oregon and the smoke clouds were coming in towards the end and it was like the most beautiful scenery. But there's really ominous because all this the sun was red a little bit towards the end. And like a different time I was in Montana, we almost had to evacuate because of a fire that was running through the mountains.

BCE: It can feel apocalyptic out there for sure. Every August or September is fire season, and it gets so gray and smokey.

EK: Yeah. It's crazy. So, even in this beautiful place there's something kind of eerie in it because it's so nice. Maybe that's just me growing up in sort of a Trash City.

BCE: It does sometimes feel more comforting to be surrounded by concrete.

EK: Yeah. So anyways, taking those photos and then sort of making them flat was interesting for me.

BCE: Yeah. Have you worked much with gouache before?

EK: I have. I do a lot of work with gouache. I really love how flat it gets and how you can go back into it and also how vibrant it is.

BCE: It might be the closest painted thing to a screen print now that I think about it.

EK: Yeah. Making the prints in Montana is amazing, but I don't really do it ever in my own practice, but I love the look of screen printing, and it's something I've always been drawn to, so I love the layering of the repetition of it, but I don't really want to do it. And I like the pace. You can't really work super fast with gouache. And for me, it's always a kind of slower process. I mean, I do work fast, but gouache slows it down.

BCE: Got to have those ways of shifting gears. Shift down, shift back up, speed it up, slow it down.

EK: Yeah.

BCE: It helps the brain. I like being slowed down a lot of times. Cool. Well, I'm so excited to see all of those in one space.