The Drunken Boat

The following is a transcription of an artist talk between Robert Kieswetter, Michele Corriel (Paul Harris Art Collection) and Tessa Granowski (Brackett Creek Exhibitions) surrounding the show that took place on August 20, 2023 at the Paul Harris and Marguerite Kirk Gallery.Brackett Creek Exhibitions: Thank you all for coming. My name is Tessa Granowski and I'll be moderating the conversation today. I'm here with artist Robert Kieswetter and Michele Corriel, the Creative Director of the Paul Harris Art Collection.

I just have a few questions for Michele first, and then Rob, and then I want to open it up to the audience for questions.

[To Michele] How did you first get in contact with Paul Harris and his family?

Michele Corriel: Tina DeWeese, who is part of the DeWeese family of artists, knew Paul Harris and knows his sons, Chris and Nick Harris. They were looking for somebody that could work with the art. And Tina suggested my name. I met with Nick at the time, and I started out writing the portfolio. Then I started putting some shows on in here. We built these walls, and… My mission is to get the Paul Harris name out there in the world and to reinvigorate his art. I like to pair his work with contemporary artists because I think his work is still relevant today, even though it was made 50 years ago or and more. I feel like there's still a lot he says to the world through his art, and there's a lot that contemporary artists can relate to. So yeah, I don't know if I answered your question.

BCE: Yeah, great. Do you mind giving us a brief bio on Paul Harris--where he was from, where he spent most of his time? How did he end up in Bozeman, Montana?

MC: Well, I'm writing biography and it’s long, so I'm going to give you a short version.

He was born in 1925 in Orlando, Florida. His mother died when he was six. If you notice, in a lot of his work, there's flowers and when he remembers his mother, it came to him through the feminine and through flowers. And a lot of his work does touch on that, various pieces besides this one.

And when he was young, he and his sister would earn extra money during the Depression by tap dancing. And the person that taught them to tap dance was Buddy Ebsen’s sister. Do you remember Buddy Ebsen from The Beverly Hillbillies? He was a very good tap dancer, and he and his sister taught tap dancing.

Anyway, so fast forward, he's 17, 18, World War II breaks out like everybody else in the country, he signs up and he joins the Navy. He served during World War II in the Pacific on the USS Ault. We have a series of his drawings that he did on the ship, which are extraordinary.

Paul Harris

Paul HarrisAt Sea, 1944

Pencil, 7 x 8”

MC (cont.): Then, like a lot of the Modernists came out of World War II and went to art school on the GI Bill, which started a lot of art departments and land-grant universities. Paul went to University of New Mexico for the first few years, where he studied with Agnes Martin. You could see some of that influence maybe in his lithographs. Then from New Mexico, he went to New York City, and he got involved with the Abstract Expressionist movement and was represented by the Poindexter Gallery, which was a big Abstract Expressionist gallery in New York. He showed there for years, and the Poindexter Gallery has a great connection to Montana. It was started by a commodity broker, George Poindexter, who was from Montana, married his wife, Elinor, Ellie, who then had a great love for Abstract Expressionists, and they opened the gallery up.

Anyway, there he became really good friends with the Elaine de Kooning and she got him a job writing art reviews for Art News. He wrote a lot of pieces and got started to get to know the art world as art writers do. Then about 1960, he got a Fulbright to teach in Chile, and in Santiago. He went down there for two years and was very happy to go down there because I guess it was a little hot in the New York world with the McCarthyism and they just really wanted to get out of this country for a little while. So, they went down there, and that's where he did all the string sculptures.

BCE: So is he already with his wife, Marguerite?

MC: They got married in 1950, I want to say. He met her at the New School in New York City.

Paul Harris and Marguerite Kirk

Paul Harris and Marguerite KirkMC (cont.): They had gone to Jamaica before Chile. One of their sons was actually born in Jamaica. And I think there was a polio breakout, so they came back to the States. Then he went again back to Chile for the Fulbright and then came back to the States again and got a job teaching in New Jersey. But he was really looking for something else. His friend, Richard Diebenkorn was in California and was saying, come out to California. This is where it's happening now. In the '60s, he did move out there to Bolinas. Eventually, with the help of some friends like Richard Diebenkorn, they helped him get some interviews with these art schools to teach. And he finally went to the Oakland California School of Arts and Crafts and taught there until he retired.

BCE: Can you touch a little more on his relationship to Bozeman and why he was out here?

MC: Paul’s wife, Marguerite Kirk-Harris, is from a family that goes back to the beginning of Bozeman. Those of you that know Bozeman will know Kirk Park and Kirk Hill and those are all related to her family. On Main Street, where there's the red barn, which is Feed now, there's a white chapel behind it, and now it's a Mexican restaurant, a little white building, that's all part of the original Kirk homestead.

Whenever Marguerite and Paul were moving around, they dropped the kids off in Bozeman at her parents' house. And they spent a lot of summers here. When he was teaching, they would come back in the summer. And he had a little studio up in Leverich Canyon. There was a little schoolhouse up there, which he turned into his art studio.

BCE: And he ended up here in the last years of his life?

MC: Yeah. Well, he had Parkinson’s, and his two sons were helping to get him through it here. Marguerite tried to come out here, but she just didn't really want to leave Bolinas.

From the Audience (Speaker #1): When did he die?

MC: 2018. And if you look at the crayon drawings, his last works were very abstract. But I think a lot of artists at some point in their career decide… abstract. I think they need the confidence of a career.

BCE: Maybe we can talk a little bit about this particular series. It's from the Fabric Sculpture series, yes?

MC: This was the end of this fabric series. But if you give me a minute, I'll run and get the quote that this is based on.

Robert Kieswetter: And I'll perform a tap dance. *laughter*

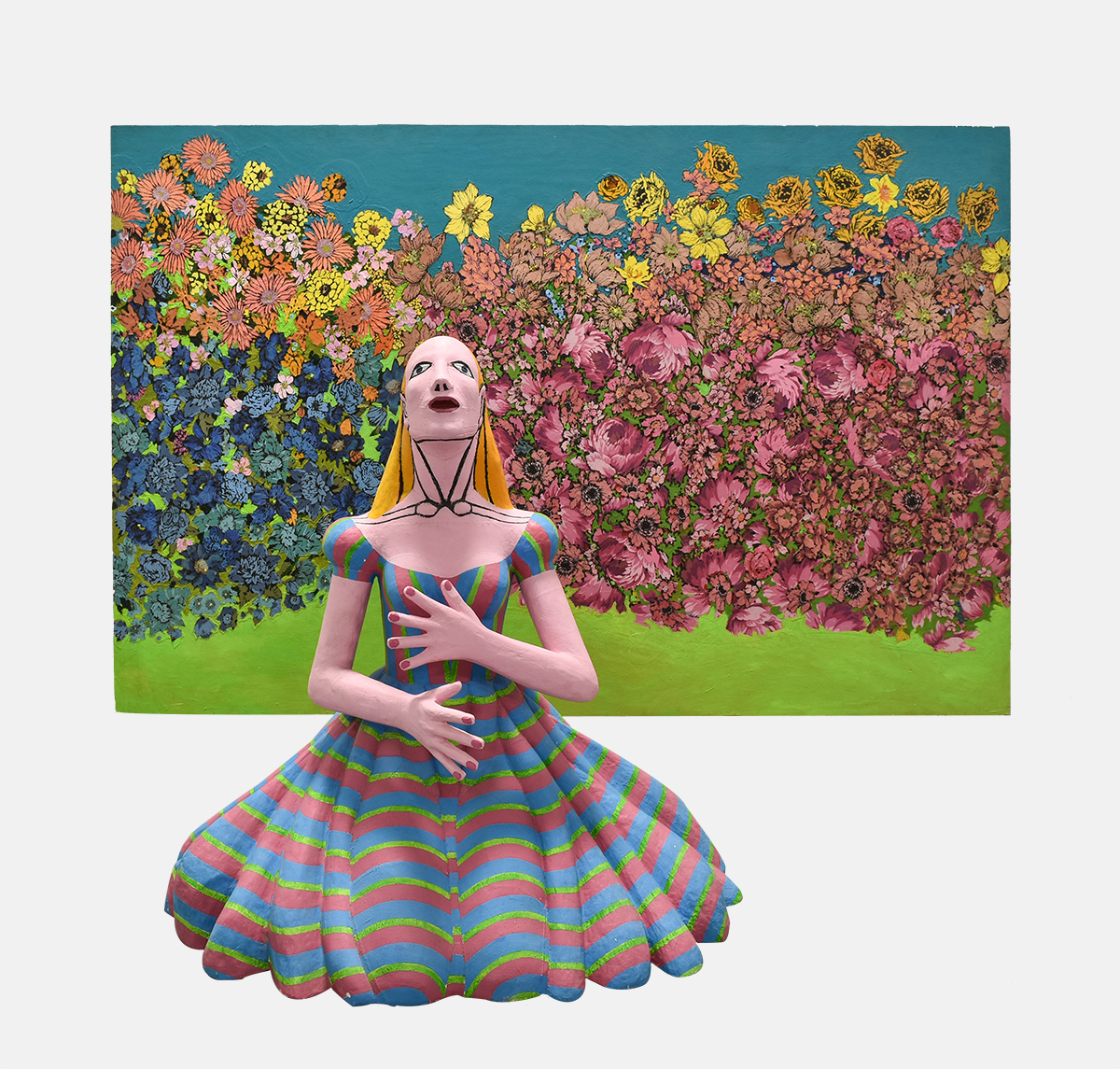

MC: The title of the piece is Strait is the Gate. It comes from Matthew 7:14, which is, “Because straight is the gate and narrow is the way which leadeth unto life, and few there be that find it.” That is what this piece is named after.**

** Update as of 09.04.2023 from Michele: I've been doing research for Paul's biography and came across an essay by Phyllis Diebenkorn that talks about Strait is the Gate. Is it influenced by a 1909 novel of the same name. Here is the summary: A delicate boy growing up in Paris, Jerome Palissier spends many summers at his uncle's house in the Normandy countryside, where the whole world seems 'steeped in azure'. There he falls deeply in love with his cousin Alissa and she with him. But gradually Alissa becomes convinced that Jerome's love for her is endangering his soul. In the interests of his salvation, she decides to suppress everything that is beautiful in herself - in both mind and body. A devastating exploration of aestheticism taken to extremes, "Strait is the Gate" is a novel of haunting beauty that stimulates the mind and the emotions.

Within the novel the passage from Matthew is quoted (as I said) but it was meant as an analogy for the small space where the woman is "throttled in her ecstasy." She wrote, "There is a fine contrast between the joyous freedom of the flowers in the background and the rigidity of the figure. In Gide's novel, the doomed relationship between Alissa and her would-be lover is revealed in a series of encounters in just such a garden."

Paul Harris

Paul Harris Strait is the Gate, 1980

Cloth, papier-mâché, plywood, 60 x 96 x 48 ″

MC: Although, I mean, to be honest with you, it's a very frightening and startling piece. I think that somebody has said in the past that it is very Alice in Wonderland type of the thing. The garden, and the tension in her hands and the lines, the seams in her face. It's very... I don't know. It has a lot of tension in it, a lot of conflicting things. Because if you look at her, she's very static and almost frightening. The background is so unbelievably gorgeous and thick and textured. If you look closely, you can see the flowers are... A lot of them are cut out fabric that are painted on. It gives it that a three-dimensional look in the background. Then with her in the foreground, it just...

BCE: Where was Paul Harris getting the fabric for these sculptures?

MC: When they first moved to Bolinas, they were on this piece of property, and next to the property was an abandoned building, a warehouse, and it was filled with this upholstery fabric, and it was free, and he was broke. And so… why not?

He was already having this practice of unconventional material sculptures. He did plaster of Paris; he did string sculptures. He was really experimenting with this idea of the medium. It just presented itself to him, and he grabbed on with both hands.

BCE: Do you know if he had a live model he was working from? Was it his wife or…?

MC: This is just me, because I've done a lot of research, but it feels like it's his mother, like it's his idea of his mother that he keeps going back to.

BCE: That was most of the questions I had in mind for you. I don't know if anyone…

From the audience (Georgia McGovern): When was this piece made?

MC: This was done in 1980, and so he was 55.

From the audience (Speaker #2): What did his mom die of?

MC: His mom died when he was six. And you know what? I don't know what it was from. Something devastating, I'm sure.

From the audience (Matthew Chambers): Are there a lot of other Biblical references?

MC: There really aren't, to be honest with you. I asked Chris what is up with this name of this piece because we had it about six different ways in our database. It was straight. Then the other strait, like the body water. Then we had “is the gate” and “like the gate”. And the gate (gait) spelled two different ways. And I was like, all right, what is this? And so then I got the Bible verse and we figured it out. But there is not a lot of Bible stuff in his work.

BCE: But there is a lot of rhyming, apparently.

MC: He loves to rhyme, and he had a really dry sense of humor. A lot of his titles are funny. You know, like Norissa Rushing. It has that “shh” sound. And Eleanor Looking For. It has that “le” or “loo” sound. And she's looking for the other earring that fell out of her ear. If you look closely, it's not there. And the visitor, I think it's historically funny.

Paul Harris

Paul HarrisEleanor Looking For, 1973

Stuffed cloth, aluminium, 127 x 124.5 x 198 in.

From the audience (Giovanni DeFendis): I have a quick question. You mentioned the Dexter collection, is that the Dexter Collection at the Montana Historical Society? The Poindexter collection?

MC: Yes, so that's the personal collection of George Poindexter. When he passed away, he had like 324 pieces in his collection. He donated half to the Montana Historical Society in Helena. The other half, to the Yellowstone Art Museum in Billings. And they are amazing. I don't know why no one has shown them. There are these pieces in there that just blow your mind. Really amazing pieces.

From the audience (Giovanni DeFendis): I called, I think, two or three years ago and just asked if I could see anything and to be in the vault. It is amazing.

MC: Do you have the book? I think it's called The Most Difficult Journey. There's an essay in it about George Poindexter being from the little town of Washington, Montana, and how he was a commodity broker, and learned how to love Abstract Expressionism. I actually make my students read it because it's so great. Because my students are from Montana, and I want them to see the journey.

From the audience (Giovanni DeFendis): It's funny. I came across it because I love Robert DeNiro Senior’s work…

MC: Yes, they have a lot of great pieces of his. And there's a great documentary that's narrated by Robert DeNiro Jr. about his life growing up with his father who was an artist.

RK: And he was an actor...

*laughter*

From the audience (Matthew Chambers): Rob, what was your reading of the work?

RK: Yeah, Michele talked about the different spellings. I've only seen one spelling, and it's S-T-R-A-I-T. And so, I took that to mean strait, like a geographic feature that separates two bodies of water… it creates a connection between the two bodies of water and thought perhaps it was a play on words.

MC: Which it probably was.

RK: Hence the comedy. And I thought a lot about the relationship of that word to his geographic position in the world at the time, which I think was Bolinas and what that could possibly mean.

I'm pretty familiar with Bolinas. I grew up in Northern California and I've done a bit of surfing there and know the geography. And there is a strait there. The residential community is called the Mesa, and it's up on a hill, on top of a cliff overlooking the ocean. Then the town itself is in the lower Mesa.

MC: It's kind of a crazy town, I’ve heard... Discovered by poets.

RK: It's cool. It was definitely colonized by poets, I think. I don't know how much you want to know about how I felt about the work or how...

From the audience (Matthew Chambers): Yeah. You had already made your work and then this was already here. So there was like a research element.

From the audience (Leila Spilman): Did you make your own work knowing this was going to be in the show?

RK: No, so I was super fortunate to be able to take a look around the collection and find something that….

From the audience (Leila Spilman): So you picked this?

RK: So, it’s the one that stuck out to me. There are other fabric sculptures. There's other papier-mâché; there's other figurative stuff. He made a lot of different types of work, but I hadn't seen this one shown.

MC: It hasn’t been shown.

RK: And so that was cool to me. I wanted to see what could happen with that. And it is pretty striking. Her back is turned to something pretty traditionally beautiful or conventionally beautiful, but her gaze is clearly fixed away from that. And we don't know what she’s focused on.

I thought there was a pretty good opportunity to create some sort of conversation between whatever I was going to include in this show as a response to what she might be focused on.

From the audience (Matthew Chambers): The background is in focus on that work and the front elements are out of focus, like you're scanning through your lens. But also, with Strait as the Gate, too. There's this blocking out of the real world for whatever mystical or ecclesiastical purpose she's looking at. But like with your paintings, they're also in soft focus. We're projecting the world to be in focus behind them.

RK: I thought whatever she was enamored by had to be less obvious or yeah, softer focus or something.

From the audience (Leila Spilman): That Bible verse is like discipline. It's meant to say that if you follow the way of God that you'll make it into the Gates of Heaven. That to me is a very natural way to be, a very Godly path, a turn to the natural world.

RK: And using the spelling of strait as I encountered it, the strait is a passageway into something that you're talking about, something bigger than...

From the audience (Leila Spilman): But what is a strait again?

RK: A strait is the point of entry between the two bodies of water. So, like a canal.

From the audience (Leila Spilman): They both flow into it?

RK: Exactly, yeah. It connects the two different bodies of water. It's sort of the gateway. The strait is the gate.

BCE: How did you choose the title of the show, The Drunken Boat?

RK: Okay. So yeah, I was trying to find a connection between myself and Paul Harris, and the most obvious one was Bolinas. And so, I was sort of swirling around the different ways... Like Michelle said, it was a magnet for poets, and thinkers, and creative types. I was going through Gary Snyder, which oddly enough we just met someone with the same name. And Richard Brautigan--I was really looking for a connection there because he had a connection to Montana, too... and somehow ended up spiraling out into Arthur Rimbaud, who didn't spend any time in Bolinas to my knowledge.

*laughter*

He was a French kid. And when he was 16, he wrote this poem called The Drunken Boat. And it is this deeply hubristic tale of the vast, giant spectrum of life filtered through the metaphor of a sinking ship. And I kept coming back to this idea of the strait being a filter between these two bodies of water. There's something happening over here and there’s something happening over there, and the strait is what decides what gets through. So, these works are all loosely based around the grid. A collection of these grids creates a filter. When presented together, they create a filter for whatever she's looking at. And so it felt like an appropriate pairing.

BCE: For most of your adult life, you've been a musician. How did you come into painting?

RK: Yeah, I guess most of my adult life I have been a musician. I've spent a lot of time in vans, and busses, and green rooms, and hotel rooms. As a touring musician, there's a lot of downtime, and that’s not the most creatively fulfilling lifestyle at times. So yeah, I started bringing notebooks… I've always been drawing and making things. I grew up in the underground, “DIY” music scene where you're making the music, you're making the artwork, you're doing the full suite of what it means to be a musician or artist in that world. And yeah, so in my downtime, I just started making small works on paper with acrylic paints and gouache and pencils. I guess I just found whatever I was lacking in the music world could be fulfilled in that downtime. So I slowly started taking it more seriously, trying to form it into some sort of practice.

BCE: And these grids started then, right? Like the paper only this big *motions a smaller notebook size paper*, but you still had the same shape or format.

RK: Yeah, these came out like what I refer to sometimes as a mindfulness practice, where they all start with two strokes or two moves. There's a vertical line and a horizontal line. It's an efficient way for me to find center… to be centered. The way that a mantra is like a nice trick to focus yourself in a meditation practice…

BCE: Or a mudra. This one's got mudra in the title.

Robert Kieswetter

Robert KieswetterMellow Mudra, 2023

Acrylic on canvas, 60 x 48 ″

RK: Yeah, so it's a nice way to get started, clear the mind, and get started, and then some formal sediment builds around those first two moves.

BCE: Does your sense of materials in these paintings still go back to when you would use whatever you had on hand? Do you find that you're more open to using whatever, like house paint, if it's there?

RK: Yeah, definitely. Most of these are made from house paint, acrylic paint, there's some oil, a lot of pet hair. *laughter* Yes, some of them were made in California and some in Montana. And yeah, the surroundings have definitely made their way into the work… I've got a lot of extra house paint lying around from fixing up a house.

From the audience (Speaker #3): And where does the pet hair mostly come from?

RK: Pet hair mostly comes from Montana.

BCE: So how long have you been coming out to Montana?

RK: I don’t know, it’s a hard question. *laughs* I guess it's been… how long have you been here, Matt?

From the audience (Matthew Chambers): Seven years.

RK: Seven years... I came right away.

BCE: And how does your sense of place show up in the paintings of where you are... Or maybe you want to point out which ones you made where, if that's important to you?

RK: Yeah, I guess these four were made here. I mean, it's like the polar opposite of a green room or the backseat of a van. You've got this vast amount of space to deal with, to contend with. And so, I guess it makes sense that it went from notebook size to whatever this size is.

BCE: *laughs* 48 by 60 inches.

RK: Yeah, I mean it’s afforded me the opportunity to stretch out, conceptually, and take advantage of the environment that you all get to live in. And I've definitely brought that home. I'm working outside at home. But even here, it's nice to be able to just find what's around and what's around helps inform what the painting ends up being.

BCE: Great. Well, that's all the questions I have…

From the audience (Matthew Chambers): You talk about sincerity in the work. I imagine the more you tour as a musician, you can’t be writing love songs all the time and performing them to people. But there's this thing where you're going to make paintings, you spend more time and you're just cracking jokes with the paintings. It seems a little wrong. That's the high school effect. Did a painting feel, or the plastic arts feel like a place you could put that sincerity?

RK: Yeah, I think for sure. Maybe that's part of the connection to the Paul Harris work because I see a little bit of that. I think it's like a lot of everything I've ever made has been a balancing act of finding some humor and some sincerity.

From the audience (Matthew Chambers): You have a love song that's called Silent But Violent.

RK: Yeah. There's a fart joke in that love song.

But yeah, I spent a lot of time being pretty concerned with making, for lack of a better term, “pop music”, with this formal language that is recognizable or accessible to a mass audience. One that's based on verses and choruses and melodies that are familiar to the Western ear. But I guess I found that with pop and the English language, there's only so far that I was willing to go to strike that balance between something that's a little bit funny and a little bit sincere. It's like a very subtle concoction for you to get the right mix. But with painting, it feels wide open. There's so much room for nuance, and that's super exciting to me.

From the audience (Matthew Chambers): Michele, did you have any thoughts about being around the show for these months? Did you make connections or see different things in the work?

MC: To me, it feels a lot that it comes down to the colors and the feeling in the room that ties it all together. For this show, we pushed the walls in, so it's a much more intimate show than a normal show than I have in the space. I really love it because the pieces are so big, all the pieces in the small space. You just feel so intimate with them. You can have a dialogue with all of them, one of them, two of them, depending on the day. It has been great to have them here.

From the audience (Tyler Macko): Rob, I saw your studio in LA and then I also saw how you work here. Making the initial cross mark, even when you're working in Jeff and Glo's barn, it was this big space and you’re still working in this small corner. Do you feel like in making that gesture, you could be anywhere in that moment? And I guess maybe that comes from the touring thing in which you had to make your own space? Even seeing your studio in LA, it is very inspiring and cool in a way in which it's just like you make the mark and then you’re in the painting. And don't have to have all this stuff. I don't know if that makes sense.

Rob’s Room in Jeff & Glo’s Barn

Rob’s Room in Jeff & Glo’s BarnRK: It definitely makes sense. I have this concept of something called Rob's Room. You're like, Oh, that's Rob's Room in the corner.

From the audience (Tyler Macko): What does Rob's Room mean to you?

RK: Rob's Room is like an easily transferable vibe zone, however you want to term…

MC: I'm a writer, so lot of people say, Oh, you must be so inspired to write in Montana. No, you're on your work. You do your work on your computer. It doesn't matter where I am, it's going to be the work. And it's not... You're not writing about the mountains.

From the audience (Tyler Macko): Do you feel like it changes the outcome of the writing?

MC: No, I don't think it does.

From the audience (Tyler Macko): Do you think it would change if you were in a somewhere you didn't want to be?

From the audience (Matthew Chambers): You're stuck on a desert island and you still write the same?

MC: Yes, I would still write the same. Because the work is coming from here. *gestures to head*

From the audience (Tyler Macko): You have your own Rob Room.

MC: And I think that's part of the artistic process.

From the audience (Giovanni DeFendis): I was going to ask, again, with the cross gesture, I don't know if it comes from the Microsoft logo. But the concept of the window, either was in or out or whatever. Is there some connection to that?

RK: Not so much. You are the second person that’s brought it up. We’re an Apple family. *laughter* No, but not specifically a window. I mean, I get that for sure. I loosely call these paintings grilles. And a grille, it can be decorative. Definitely in a window, you call that a grille, or the front of a car… But it has a functional meaning, too. It can be a grate that keeps matter from passing through to another location. But yes, I haven't thought about it specifically as a window, but that makes a lot of sense.

MC: There is an art historical trope of the window that is played out in many, many ways by many artists.

RK: Not by me.

*laughter*

MC: But when I look at this one, I don't see it as a window. I see it as four converging things. I see the edges more than I see it as a single. That's just me.

BCE: Some of these titles, they're pretty funny. In your titling process, is it something like with songwriting, or is it something where it's completely separate? How do you come up with some of these titles for your paintings? Yeah. Maybe we can say some of them... Ernest Goes to Church, Mellow Mudra, High on Port Sudan...

RK: They are all sort of inside jokes to someone or another. Ernest Goes to Church. Eric Mast, who I think most of us know in this room, when he saw that title, he's like, I think this title is just for me. I think he was probably right.

Robert Kieswetter

Robert KieswetterErnest Goes To Church, 2023

Acrylic, oil and gouache on canvas, 60 x 48 ″

BCE: We don't have to know the inside joke.

RK: Well, are you familiar with the Ernest Goes To franchise?

MC: Yeah, they are a bunch of really bad movies.

RK: I mean, come on, really bad is a stretch. Well, Ernest was a character played by the actor Jim Varney, who a serious actor.

MC: I thought he was a comedian, but I could be wrong.

RK: And a comedian, but he took it seriously. He hit it with this Ernest character.

MC: Yes, he certainly hit something.

RK: And to my knowledge, they never made Ernest Goes to Church. I thought that might have been a good sequel and I knew Eric would get a kick out of it. But yeah, the titles come usually last.

MC: Titles are always last. Unless you have a stroke of genius.

BCE: Any other questions from the audience?

From the audience (Jonathan Beaumont Thomas): Rob, you've kid of already touched upon this, but do you really separate these out from your music completely? Do you feel like these are fulfilling a different creative need? I don't look at these and think of them as being particularly musical. They certainly have structure, and composition and you could go to that place, but it doesn’t hit you over the head or anything. Is it really something separate creatively for you or could you talk a little bit more about that?

RK: Yeah, I think it is pretty divorced from music. I think making music has become a day job or a punch the clock sort of thing or can become that way pretty quickly… That's interesting. I haven't thought about that specific question, but I'm still asking the same questions or thinking about some of the same ideas, but the composition or... Yeah, they're composed in a, for lack of a better term, much more abstract way.

From the audience (Matthew Chambers): Like you’re not thinking about an audience?

RK: I'm not thinking about an audience, and I'm not thinking even about how it gets consumed at the end when the product is finished. Whereas with music, it's almost impossible for me not to think of that full arc of the piece.

MC: Can you hear them?

RK: That's a good question. It's tough because I consume media when I'm making them, so I think I sometimes hear remnants of that.

From the audience (Tyler Macko): You just only watch the Ernest movies.

RK: Yeah. *laughter* No, I don't think I hear them in a traditional sense.

MC: Some people can hear colors…

RK: Yeah, I'm not synesthetic.

From the audience (Georgia McGovern): Did that title come after you learned that the title for this Paul Harris piece was Biblical?

RK: I actually didn't know it was Biblical. I don't know how I missed that, actually. It's also the title of a novel, too.

So, I called this grouping of paintings the Loose Sluice. And that came after thinking about that (Strait Is The Gate). I grew up in a gold mining town, and the sluice box is very prevalent in that area. A sluice box is a device you send the gravel through, a series of filters, basically, and you can get the gold at the end.

MC: You hope to get the gold at the end.

From the audience (Tyler Macko): You see the paintings as the actual sluice or the gold in the end?

RK: The grouping is like a loose, loose being a really liberal, a generous thought, like a lot's getting through. Right. So the painting is, I guess the sluice.

BCE: The dirt is the gold.

From the audience (Matthew Chambers): When you paint, is it the gold? Are you Rob, the artist? Like you wouldn't want to play guitar and think like, oh, Neil Young. Woody Guthrie. But it's like you can just put on a Beret. It's like the generic Halloween costume.

RK: Yeah. I think in everything, so much of it is about creating the Rob's Room. And so much of it is that process of getting the zone dialed in and getting ready to... So, in that case, I guess, yes, I don't ever think of it that way, but it's the same as putting on the wetsuit or tying up the boots or whatever, like that same type of ritual, I guess, ends with being the artist. But it's also the same thing I go through to be the gardener or... I don't know. But the beret does look good. *laughter*

From the audience (Speaker #4): You're talking about the filter and you're trying to just get to the core of when you're painting. You're just trying to meditate and get to a sense of peace or a sense of...?

RK: I think just a sense of something. It doesn't have to be peace. That's too much to ask for, that representation of peace.

From the audience (Speaker #4): The core of this thing that’s inside you... you’re trying to access that?

RK: I guess so. I feel self-conscious saying that, Yeah, this is it. This is the core. But yeah, I guess so, in a sense. That's the goal. It's maybe not 100% successful…

From the audience (Speaker #4): Yeah, we don't get that with your writing *gesturing to Michele* because the writing is for someone else, but this is for you.

From the audience (Tyler Macko): Yeah, I mean, you're the sluice. And these are the... [dirt/gold].

RK: I hope that answers it. I don't know the answer exactly, but I think that's the best we can hope for.

From the audience (Giovanni DeFendis): Sometimes as an artist, I'm afraid of finding the answer. Because then it's like, okay, well, that's not it. Exactly. So, yeah. That's the whole talk.

From the audience (Leila Spilman): But you don't use Microsoft.

RK: Oh, right. I'm not familiar. It's so confusing. There are so many colons and slashes...

BCE: I think we can maybe wrap it up there. Thank you guys so much for coming and for the great questions!